H.L. Green — January, 1895

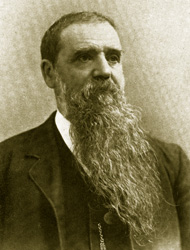

James A. Greenhill, whose portrait appears to the left, is a citizen of Clinton, Iowa. He is not renowned for great scholarship, for remarkable achievement or for wonderful intellectual powers, but he is in the best sense of that often used term, a thoroughly self-made man—or in other words he is one of Nature’s noblemen. December 29, 1828, he first saw the light of day in Glamis, Forfarshire, Scotland, a little village of some two hundred inhabitants. In his youth his educational advantages were quite limited, and he acquired very little that would be called school education; but he possessed a remarkable inquiring mind, and he imbibed knowledge and practical information at first hand from the great book of nature. In his boyhood days he served an apprenticeship with his grandfather as wagon maker—he had a mechanical insight that enabled him to soon acquire proficiency in any line of inquiry, and he soon became a first class wagon maker. His ancestors were of the old Scotch Presbyterian school, inclined to superstition, but not very bigoted and about all that they required was that one should profess religion, and attend church on the “Sabbath.” They had no “family worship” during the working days of the week; but on Sunday morning- the family would form a semicircle around the fireplace, and each read a few verses from the Bible—two or three chapters generally. They each had to commit to memory the Westminster shorter catechism. That exercise was considered sufficient to keep God on good terms through the week, and insure their passport to heaven if any of them should happen to die during the next ensuing seven days; so that in fact there was not much superstitious restraint resting upon the mind of the subject of this sketch.

James A. Greenhill, whose portrait appears to the left, is a citizen of Clinton, Iowa. He is not renowned for great scholarship, for remarkable achievement or for wonderful intellectual powers, but he is in the best sense of that often used term, a thoroughly self-made man—or in other words he is one of Nature’s noblemen. December 29, 1828, he first saw the light of day in Glamis, Forfarshire, Scotland, a little village of some two hundred inhabitants. In his youth his educational advantages were quite limited, and he acquired very little that would be called school education; but he possessed a remarkable inquiring mind, and he imbibed knowledge and practical information at first hand from the great book of nature. In his boyhood days he served an apprenticeship with his grandfather as wagon maker—he had a mechanical insight that enabled him to soon acquire proficiency in any line of inquiry, and he soon became a first class wagon maker. His ancestors were of the old Scotch Presbyterian school, inclined to superstition, but not very bigoted and about all that they required was that one should profess religion, and attend church on the “Sabbath.” They had no “family worship” during the working days of the week; but on Sunday morning- the family would form a semicircle around the fireplace, and each read a few verses from the Bible—two or three chapters generally. They each had to commit to memory the Westminster shorter catechism. That exercise was considered sufficient to keep God on good terms through the week, and insure their passport to heaven if any of them should happen to die during the next ensuing seven days; so that in fact there was not much superstitious restraint resting upon the mind of the subject of this sketch.

As he grew to manhood he read and learned of the great country of the West, known as the United States of America, where liberty prevailed, and where the opportunities for intellectual advancement and material success were far superior to those in the old country; and he resolved to go there and avail himself of those superior advantages, and on November 4, 1850, he bid farewell to his kindred and personal friends and to his native land and took passage on the ship Arctic, and after a passage of fifty days on the ocean landed in New York City, January I, 1851. His first employment in his new home was house carpentering. In 1852 like a sensible young man he chose him a wife and was married, and in 1856 by naturalization became a citizen of this country, and cast his first vote for John C. Freemont for president of the United States. The next year after his marriage he moved to the growing city of Chicago, and engaged in that branch of carpentry known as stair-building, which business he has followed ever since. In 1873, having acquired a good property by his trade, or profession, he removed to his present home.

Up to this time, 1873, he had been so much engaged in business that he had paid but little attention to religion—as our Christian friends would say he had “neglected his soul’s salvation”—had nearly forgotten that he had one. During all these years he had dealt honestly with his fellow men, had paid his debts promptly, had never wronged any one, had lived an upright life; still he thought the faith of his parents must of course be the true religion, and somehow the old book that they used to read around the hearthstone must of course be God’s word. But about this time he met with a “change of heart,” or more properly, of opinion. We will allow our friend to state how it came about:

In 1879, by accident I read Ingersoll’s “Mistakes of Moses;” and that set me to examining, what I had heretofore considered a part of God’s word, known as the writings of Moses. I desired to ascertain if Robert had given Moses a fair “shake,” and I could not see that “Bob” was taking any unfair advantage of him, and this set the matter in a somewhat different light from what I had been in the habit of looking at it; although I now, in looking back, feel quite sure I was never very orthodox, for I remember that when our first child was born in 1853, and my wife began to talk about christening, I took the ground that the ceremony was Romanish, and I did not believe the child would be any the better for it; but I said to her if she desired it I would not object_ Shortly after the subject was dropped, and we have had no water mark put upon either of our four children. In 1880 I read Paine’s Age of Reason, and that left me free from orthodox superstition and now I have no use for Bibles or priests.

In a private letter Mr. Greenhill gives the following account of a trip he had through Canada and to Boston:

In January, 1885, in going through Canada, I stopped a day or two at Kingston, at the foot of Lake Ontario, and while there visited the penitentiary, and from a little conversation with a guard who told me he had been there fifteen years, I learned that in all that time he had never known of an Infidel convict there, and only three Jews, quite a Christian institution you see. The day following I visited the Paine Memorial, in Boston, where I had the pleasure of meeting J. P. Mendum, Horace Seever, Ernest Mendum and John A. O’Malley, and enjoyed with them a session of the Ingersoll Society.

In the same letter he writes as follows of a visit to the land of his childhood:

In 1888, after an absence of thirty-eight years, I crossed the Atlantic to visit the “Scenes o’ my Childhood,” and in that trip had the pleasure of contemplating the progress made in ocean navigation since I came in 185o. At that time it took me over seven weeks to come from Liverpool to New York; but now we went from New York to Liverpool in less than seven days. I spent a week in seeing the sights in London, and then went up to Scotland, in time to meet my brother and sisters on the sixtieth anniversary of my birth and had a very pleasant meeting. I found the village unchanged; recognized no one, not even my brother and sisters. On the week beginning January 20, visited Edinburgh, Melrose and Dryburgh. In the Abby at Dryburgh I saw the graves of Sir Walter Scott, his wife, son and Lochart, his biographer, all close together protected by an iron railing. Next visited Abbotsford, Glasgow and Dumfries and in the graveyard, at Dumfries, entered the Mausoleum in the vault of which lie the remains of Robert Burns and his family; also visited Lincluden Abbey., near Dumfries, and reached Ayr on the 24th. On the 25th, the anniversary of the poet’s birth, visited the cottage near “Alloa’s Auld Haunted Kirk,” where he was born. Among other things, and occupying a conspicuous place, is a poem by R. G. Ingersoll, evidently composed in the room. The bedstead stands in the corner, the old eight-day clock is there, a few plain chairs and pine cupboard complete the furniture of the room, which together, with the old fashioned fire-place, takes us back in imagination Jco years. Next visited the “Auld Kirk” and saw the “Winnock Bunker i’ the East,” where Tam O’ Shanter saw Auld Clootie playing the bag-pipes, the night he broke up the seance, when “Cutty Sark” was playing high jinks. In the graveyard, between the road and the Kirk, is a mound and tombstone showing where lie the remains of Wm. Burness, the father of the poet. Next visited the “Auld Brig O’ Doon,” where Maggie lost her tail; also the monument in the garden, in sight of the “brig.” And about the middle of February returned to Clinton, Iowa.

Being fond of scientific pursuits, and having fully mastered geometry in connection with my work; I got restless for something new, so in 1892, I had a telescope seven and a half feet long, with a six inch object-glass, made by Alvan Clark, which, including finder, diagonals and oculars, cost me $500. Before that I had owned a similar one. My observatory, stand and equatorial cost me nearly $500 more, and now I have an excellent companion for my leisure hours, and am prepared, and at all times ready to accommodate investigators to a view of some of the beauties of the heavens, day or evening when clear, at my home in Clinton.

James A. Greenhill, as will be seen, has not acquired a national reputation, but he has what is much better, a good reputation, where ever known, and those who know him best think the most of him. Notwithstanding his extremely heretical opinions he commands the respect of all his intelligent Christian neighbors. He often invites them and their children to his splendid observatory to view the planets through his large telescope, that they may know more of the great book of Nature, which to him is the only Bible that can rightfully be characterized as divinely inspired. He is generous to a fault. He is true to his own convictions. He respects the honest opinions of others. He detests hypocrisy and cant, is a lover of Nature and of Truth and Justice, and although he has no belief in the orthodox God, the orthodox devil or the orthodox hell, he is constantly doing all in his power to rescue mankind from present earthly hells and build up a Kingdom of Heaven right here on this solid earth. It would be well for the world if there were more such friends of Humanity as James A. Greenhill. He passed away at his home in Clinton, Iowa on November 19, 1906.