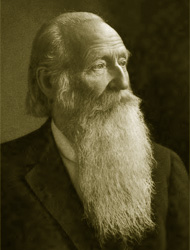

By J. M. Peebles, M.D. — November, 1900

Fancying the name of the Free Thought Magazine, and having been a Free Thought Spiritualist for these fifty years and more, and further having had the pleasure of this journalistic editor’s acquaintance for a full half century, may I claim sufficient hospitality for the insertion of several articles in your journal in the elucidation and defense of Spiritualism, as I understand it? Under no consideration would I presume to speak for the great body of Spiritualists, as I differ radically from many of them. To me naturalism and Spiritualism are in perfect accord.

Fancying the name of the Free Thought Magazine, and having been a Free Thought Spiritualist for these fifty years and more, and further having had the pleasure of this journalistic editor’s acquaintance for a full half century, may I claim sufficient hospitality for the insertion of several articles in your journal in the elucidation and defense of Spiritualism, as I understand it? Under no consideration would I presume to speak for the great body of Spiritualists, as I differ radically from many of them. To me naturalism and Spiritualism are in perfect accord.

Spiritualists, unlike churchmen, have no tutelary, human-shaped God to worship, no iron-clad creed, no priest-conceived confession of faith; but have a general declaration of principles, which probably a large majority of them accept. Upon one point all Spiritualists agree; and that is, the continuity of life. They compare death to a rose, that, climbing up some garden wall~ blooms on the other side; or to a bridge, the crossing of which opens into a world of conscious verities, peopled with innumerable intelligences. and with better facilities for development than in this preliminary stage of existence, where the poor often beg for bread, where hearts often ache and tears often flow.

If Divine Energy—Evolution—has lifted us up through long gone ages from and through lower kingdoms; if it has pushed or pulled us, just as you please, thus far up onto the pinnacle of rational royal manhood, and endowed us with towering aspirations for further unfoldment, why should this benevolent law suddenly stop at death’s door and drop us, consign us to the terrible doom of an eternal and merciless non-consciousness? Trust in the uniformity of nature and in the continuity of its· processes, leads not only to a different, but to a far more rational conclusion. In these clear, pensive October evenings I look up to those glittering, shimmering star-worlds, the moon with its extinct volcanoes, Mars with his canals, Saturn with his golden rings, and say to myself, Oh, how grand to see, to study the cosmology of planets heretofore unpressed by human feet; and further how delightful to meet over there my old friend of the Free Thought Magazine, and with him, relieved of the silica, iron, phosphorus, lime and other physical constituents, traverse together the ever-multiplying spaces of immensity. Is there an ideal that cannot become real?

The body has its uses in this primary stage of being, something as the husks have theirs while the corn is growing. But the body is not the man. I ·never knew a corpse to bury itself nor to plant evergreens over its grave. At death the conscious man vacates, moves out of its temporary tabernacle. Clairvoyants see it in the process of moving. Because others cannot is their misfortune. We sympathize with the wayside blind man, who cannot see the sun. “Where shall we bury you?” said the disciple, Crito, to Socrates when he was dying from that drastic hemlock poison?

“Bury—bury me,” exclaimed the dying philosopher, “bury me just where you please if you can only catch me;” then he added, “Have I not often told you and the wise men that this body is not Socrates.” My sainted mother at eighty-nine, while sitting in her chair, slept into the higher life. Leaving her earthly tenement and catching glimpses in this birth-hour, of the spiritual world, and beholding the forms of welcoming friends, her own death-chilled face became wreathed in smiles. It was the soul’s victory. In all my public life of fifty-nine years I have never seen the dying weep. The Hindu priest, while baptizing the infant in Ganges’ waters, says, “Child, precious little .one, you came into the world weeping while all around you smiled. May you so live the true, divine life, that departing, you may smile, while all around you weep.” What mortals dolefully denominate death, the risen, robed in immortality, pronounce birth.

In the struggles and death-spasms witnessed in the last hour of mortality there is no pain. The nervo-contortions, the slow, deep breathings are but the efforts of the real thinking man to release himself from the disease-impaired tenement, unfit for further use. Study nature. In the hatching process, the growing, restless, unhatched bird twists and struggles to break away from its shell. The shell only dies. The released bird, retaining its individuality, soon makes music in the lilac bush or the faraway forest.

The bodies of human beings die-not because some unhistoric Adam in a mythic Eden sinned, nor because the war-inspired Napoleon crossed the Alps; but because they are physical organizations composed of atoms, molecules, cells and varied other earthly substances; and, it is an immutable law that all such organized forms must in their time become disorganized, earth to its earth. Life and death, comparable to the co-related forces of being, are both equally beautiful when fully comprehended as the positive and negative sides of nature.

Ex nihilo, nihil fit—”from nothing, nothing comes”—is axiomatic. We laugh at the old Calvinistic dogma that God made the world in six days out of nothing; but if nothing cannot be made, or cannot become conscious, rational something or substance; the converse, logically considered, must be equally true, that something, conscious substance, real rational, substantial men cannot become nothing. Annihilation is unthinkable. The universe knows and can know no absolute loss. The word annihilation has fully given place to transformation. Once out, absolutely out of real, conscious existence, never in; and once in, never out, into unreasoning, incomprehensible nothingness.

The good and the true do not even for a moment in dying lose their consciousness. The erudite Judge Edmonds, of New York, whose spirit séances I occasionally attended a generation ago, had a warm personal friend in the Quaker Abolitionist Isaac T. Hopper, who for months had been confined to his house by a lingering disease. The Judge, frequently calling, saw him one afternoon, and, though quite low, he conversed cheerfully, and the Judge thought he might live for weeks and months. At seven o’clock the same evening the Judge held his usual Thursday evening séance. An invocation was offered and almost immediately the hand of the Judge’s daughter, Laura, was seized by some unseen force and wrote speedily, automatically, “I am in the spirit world.—I. T. H.” “Who can this be?” was the passing inquiry. The Judge, looking, said, ”Those are the initials of friend Hopper, but it can hardly be him, as I saw him but a few hours ago, and, though feeble, he seemed quite comfortable. It will take but a short time, I will go and see,” exclaimed the Judge. He found Hopper dead. Returning soon, the lady’s hand again wrote, “I am in the spirit-world and I quite fully understand now what the Apostle meant when he said, ‘We shall not all sleep, but shall all be changed.’ I have changed worlds, and met my friends that had passed on before.”

This was not telepathy, not mind transference, nor miracle, but the direct testimony of one who had crossed the crystal river and reached the evergreen shores of that better land, of which poets had sung, prophets foretold and the existence of which, the intermediaries of to-day, demonstrate. From the testimonies of the dwellers in those higher, invisible realms of being, I feel justified in saying that spirit-life is an active life, a social life, a retributive life, a constructive life, and a progressive life; consciousness. memory, reason and aspiration accompanying us thither.

The spirit-world is here. We are spirits incarnate now, crossing the bar, as Tennyson called it, we shall be spirits decarnate; having stepped up one step higher in the stage of evolutionary life. In those spirit spheres there are refined etherealized fields, forests, fountains, gardens, groves, meandering streams, schools, lyceums, conservatories of music, massive libraries, art galleries, educational universities, congresses of angels, parliaments of savants and seers such as Confucius and Plato, Jesus and Epictetus, the Phrygian philosopher—everything to charm, to intellectually unfold, and spiritually enrich the once inhabitants of earth. These, and million other realities, refined, sublimated and adapted to those higher spiritual states, obtain in those up-realm spheres of a measureless infinity. This article must be considered as but preliminary.